Private student lending can be a valuable member service and a good source of revenue for credit unions when done safely and soundly. However, PSLs have unique features and risk characteristics that are unlike most other consumer loan products, and which must be properly understood and managed.

Credit unions have been increasingly engaging in private student lending. Since 2011, when NCUA first began collecting Call Report data on private student loans (PSLs), the outstanding PSLs within the credit union industry have grown 33 percent, from $1.5 billion to $2.0 billion. In addition, four credit union servicing organizations (CUSOs) have been created to assist credit unions in originating, servicing, and participating in PSLs.

Thus, the enclosed Supervisory Letter provides guidance to field staff on examining PSLs and analyzing the associated risks. The Supervisory Letter provides an overview and background about PSLs and defines field staff responsibilities with regard to reviewing PSL programs, including ensuring that credit unions meet certain risk-management expectations with regard to PSLs. Also enclosed is a new questionnaire that will be incorporated into AIRES to assist field staff in conducting exams of credit unions involved in private student lending.

If you have any questions on this Supervisory Letter, please direct them to your immediate supervisor, regional management, or state supervisory authority.

Sincerely,

/s/

Larry Fazio

Director

Office of Examination & Insurance

Supervisory Letter — Private Student Loans

1. Introduction

Credit unions are increasingly using private student loans (PSLs) to diversify and increase loan portfolios. Field staff must understand the characteristics of PSL products to determine whether credit unions have established appropriate risk-management practices. This Supervisory Letter serves as a reference tool for field staff as they review PSL programs. The guidance within this document applies only to private student loans as defined in the Background section.

2. Background

Lenders make private student loans, also referred to as non-federally guaranteed student loans, to help students fund qualifying post-secondary education. Student-borrowers may use a PSL to bridge the gap in funding that exists after they have obtained federal student loans and grants. It is important to note that PSLs typically do not carry backing from federal, state, or local jurisdictions.

Private student loans have characteristics and risks that are unlike other consumer-based loan products. For example:

- PSAs have long-term maturities with a unique purpose-based repayment structure to meet the specific needs of education financing. PSLs often have a deferment period that allows a student-borrower to postpone repayment, pay for interest only, or pay a fraction of the interest while he or she attends school (and a grace period of six months after graduation).

- Some PSLs are structured as a line of credit while the student-borrower attends school, and convert to a closed-end loan once school attendance and the subsequent grace period are completed.

- PSLs are exempt from discharge during bankruptcy under most circumstances.1

- Student-borrowers generally have little demonstrated credit history.

- PSL repayment typically is dependent on an expectation of future employment and income.

- Many PSL lenders rely on co-signers (often the student-borrower’s parents) to compensate for the added risk involved with lending to unemployed borrowers who have limited credit history.

Private student lending programs have a wide variety of terms, conditions, and underwriting standards. Field staff should familiarize themselves with the particular program offered by a credit union to understand the associated risks. As with the underwriting and origination process, loan terms and repayment conditions may vary. Interest typically accrues during deferment and capitalizes when the borrower enters repayment.

Each private student loan program has its own standards and requirements that govern loan disbursements to student-borrowers.2 As a matter of sound practice, loan proceed checks are generally made payable to the student-borrower’s college or university, and are often sent directly to the educational institution.

Appendix A provides additional background information on PSLs, including:

- differences between PSLs and federally guaranteed student loans,

- historic milestones in the development of PSLs, and

- current trends and status.

Credit unions may originate private student loans either directly or indirectly through a third party (including via loan participations). Appendix B compares direct PSLs with indirect PSLs in more detail.

3. Private Student Loan Risks

As with any type of lending, a credit union’s PSL program can affect all risk areas (credit, compliance, interest rate, strategic, transaction, and liquidity risks). However, PSLs have relatively unique characteristics that add additional risk-management and operational challenges in managing credit, interest rate and liquidity, transaction, and compliance risk. Thus, field staff needs to ensure that credit unions

- understand the associated risks and support their PSL programs with sound planning, policies, and controls; and

- have the necessary expertise and infrastructure to establish strong internal controls over a PSL program.

Credit Risk

Private student lending can involve significant credit risk, especially if the lender has weak underwriting and collection practices. The level of credit risk in student lending is reflected in the fact that, historically, both federally and non-federally guaranteed student loans have elevated levels of delinquency and default rates compared to most other forms of consumer lending. The key characteristics of PSLs that contribute to credit risk are:

- The student-borrower’s ability to repay is unknown until the student separates from school.

- Projecting portfolio performance and making needed adjustments to underwriting and other standards can be challenging because PSLs have long periods of little performance data while the student-borrower is in school (and during any grace period), and long maturities after graduation. Repayment often occurs over periods of more than 20 years; during this time, many changes, in the economy and in a borrower’s individual circumstances, can occur that would affect their ability to repay.

- PSLs are not federally guaranteed.

To mitigate these risks, field staff needs to ensure that credit unions:

- Establish loan policies with sound underwriting and collection requirements (e.g., debt ratio limits for co-signers, if applicable; individual loan limits; school certification of expenses; etc.);

- Implement an ongoing quality control process to ensure PSLs meet the credit union’s underwriting standards;

- Provide various limits (e.g., on concentrations of loans per school, annual loan growth, total size of PSL portfolio) to control the level and concentrations of credit risk, especially as a credit union develops experience with this type of lending;3

- Develop plans that include exit strategies for facets of the PSL program, such as schools with high default rates and third parties that are not performing adequately; and

- Conduct regular and ongoing portfolio analysis. In addition to evaluating and monitoring traditional portfolio metrics (e.g., delinquency rates), the credit union must have good systems to monitor deferments, forbearances, and restructurings, and the performance of specific segments (cohorts) of the student loan portfolio.

The graduation rates, employment prospects, and income potential for the student-borrowers largely determine the performance of student loans. These variables are heavily influenced by the economy (job market), the student’s field of study and degree, the academic performance of the student, and the reputation of the school the student attends. Thus, the performance of PSLs can vary significantly by cohort (e.g., field of study and degree, school attended, and graduation year relative to the economic cycle).4 Field staff needs to ensure credit unions fully evaluate the credit risk of their PSLs by conducting a risk analysis for the different cohorts.

Credit union management can select from a variety of loan portfolio analytical tools to monitor the credit union’s PSL portfolio properly.

- Static pool, or “vintage,” analysis helps determine the true performance of loans by isolating a fixed group of loans for analysis to hold relatively constant key variables that affect loan performance, such as the economic cycle and underwriting criteria used during the period.

- Multidimensional portfolio analysis groups loans by risk factors and cohorts like origination date, credit score, school, academic discipline, field of study, and so forth.

- Cohort analysis typically includes measuring defaults over a two-year period, immediately after a cohort of student-borrowers enters repayment.

- Cohort default rates (CDRs) indicate the level of borrowers attending a certain school who have defaulted on their loans within a specified amount of time after entering repayment. Federal law requires the Department of Education to use the cohort default rate to determine a college’s eligibility for federal student aid programs. Institutions that have at least 30 borrowers entering repayment in a fiscal year and a cohort default rate higher than 40 percent in a single year, or higher than 25 percent for three consecutive years, cannot participate in most federal student aid programs.5 Similarly, credit unions can reduce risk by limiting their exposure to students at schools that have a high default rate.

Interest Rate and Liquidity Risk

The unique characteristics of PSLs can affect a credit union’s interest rate and liquidity risk. Long-term, fixed-rate PSLs can pose interest rate risk similar to mortgage loans. Variable-rate PSLs may contain lifetime and periodic caps that limit a credit union’s ability to reprice these loans.

While student-borrowers are in the deferment period, cash flows on PSLs may be negligible. Projecting future cash flows can be challenging because PSLs have historically high default rates, and the borrower may have additional deferment options based on the how the program is structured. As a result, field staff need to ensure that credit unions that offer PSLs have a strong asset/liability management (ALM) program.

Compliance Risk

Private student loans are subject to the Federal Credit Union Act, NCUA’s applicable lending regulations, applicable state law requirements, and a variety of consumer compliance laws and regulations, including:

- Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C.),

- Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005,

- IRS Internal Revenue Code of 1986,

- US Bankruptcy Code (11 USC 523(a)(8)),

- Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z),

- Electronic Funds Transfer Act (Regulation E),

- Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (Regulation F),

- Privacy Act of 1974,

- Equal Credit Opportunity Act (Regulation B), and

- Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices (Regulation AA).6

The type of disclosures that must be provided to a student-borrower and the loan maturity limits for federal credit unions under the Federal Credit Union Act depend on whether the loan is a closed-end or open-end loan.

- Closed-end private student loans must comply with the “Private Education Loan” disclosure requirements outlined in the Truth in Lending Act, Subpart F, Special Rules for Private Education Loans.7 For federal credit unions, the loan maturity cannot exceed 15 years from origination.8 Any relevant state law would govern maturity limits for federally insured, state-chartered credit unions.

- Open-end9 private student loans must comply with the regular open-end account opening and periodic disclosures called for in Subpart B of the Truth in Lending Act.10 For federal credit unions, open-end PSLs are not subject to any maturity limit.11 Any relevant state law would govern maturity limits for federally insured, state-chartered credit unions.

Field staff must ensure that the credit union’s PSL disclosures comply with Section 433 of the Higher Education Opportunity Act.12 In addition, advertising, marketing, lead generation, and referral fees must comply with applicable regulations and supervisory guidance.

The refinancing of multiple student loans owed by a borrower into one consolidated student loan is a consumer-friendly practice, and may improve collectability by lowering the borrower’s costs. However, while permissible, there are additional compliance and disclosure considerations when a credit union offers to consolidate both private and federal student loans. Federal loan programs carry benefits a borrower loses when a federal loan is refinanced into a private consolidation loan. Thus, field staff needs to ensure that the credit union’s student loan policies and procedures address consolidations. Field staff will determine that the:

- credit union’s consolidation practices and disclosures, including advertisements, have undergone appropriate legal review to ensure the materials meet applicable laws and regulations, and that credit union members understand the terms and conditions offered; and

- credit union adequately discloses the terms of consolidation, including the potential for a borrower to lose eligibility for certain types of deferment and to lose eligibility for certain cancellation or loan forgiveness programs.

Transaction Risk

Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL)

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) ASC 450-20, Loss Contingencies, is the primary generally accepted accounting principal (GAAP) governing reserving for losses on PSLs. Calculating appropriate ALLL reserves for PSLs has additional challenges associated with limited historical performance data on student loans, particularly those in the deferral period.

Field staff must ensure the credit union’s ALLL methodology properly accounts for any PSLs held by the credit union. In particular, field staff must confirm that the credit union considered default rate trends as part of the quantitative and environmental adjustments to the historical loss rate for PSLs.13 In addition, field staff must confirm that a credit union that has no historical experience offering PSLs follows guidance in the 2006 Interagency ALLL Policy Statement and FAQ issued in December 2006.14

Income Recognition and Nonaccrual

In general, a credit union can accrue interest on PSLs during the deferment, or draw, period if the PSL program substantially meets the revenue recognition requirements in GAAP.15 These loans are not assigned an adverse credit risk grade or put on nonaccrual during the draw period while the borrower qualifies for student status unless something happens to cast doubt on the loan’s collectability (e.g., the student dropped out of school). If the contract specifies the deferred interest adds to principal, field staff should ensure that the credit union increases (debits) the loan receivable during the deferment period for the accrued interest.

Once a student-borrower is out of school and in the repayment period, a PSL is treated like any other consumer loan: It must be placed on nonaccrual at 90 days or more past due and accrued interest may not be capitalized. Interest accrued once a PSL is in repayment (post-draw period) would be reversed or charged-off when the loan reaches 90 days or more past due, and cannot be restored for financial reporting purposes unless it is received in cash, consistent with NCUA regulations.16

4. Other Private Student Loan Program Considerations

Use of Third Parties

Credit unions may contract through a credit union servicing organization (CUSO) or other third party to administer part or all of a PSL program. In many instances, third parties perform the underwriting, pricing, and servicing of the loans.17 Third-party relationships can be essential to help credit unions become their members’ primary financial institution; however, inadequately managed and controlled relationships can result in unanticipated costs, legal disputes, and financial loss.

Credit unions are ultimately responsible to ensure that third-party vendors comply fully with applicable laws and regulations. Field staff needs to ensure that the credit union assesses and understands the third-party relationships, and has taken steps to mitigate the risk exposure a third party may pose in the event it fails to perform. Field staff will evaluate management’s due diligence process around compliance and service quality of third-party programs as part of their review.18

In particular, field staff needs to ensure the credit union has:

- evaluated the financial capacity of a third party to meet the broad financial obligations of the contract;

- ensured the third party meets all legal and regulatory requirements to provide the service in all states where the credit union provides service to members; and

- included provisions in the contracts that require the third party to provide adequate reporting so the credit union can monitor and account for the PSL program.

Default Insurance

Some PSL programs include default insurance policies that protect the credit union against loss if a loan is not repaid according to contract terms. The default protection usually activates once a loan becomes a certain number of days delinquent provided the servicer followed the prescribed collection procedures prior to that point. Field staff needs to evaluate a credit union’s due diligence of default insurers, including understanding how the insurance works, any conditions that the lender-servicer must meet for the coverage to remain in force, and that the insurer has the financial capacity and legal authority (e.g., can operate in the applicable state) to perform under the contract.

Loan Participations of PSLs

Revisions to NCUA Rules and Regulations Part 701.23, Loan Participations; Purchase, Sale and Pledge of Eligible Obligations, and Part 741.8, Purchase of Assets and Assumption of Liabilities, became effective September 23, 2013. Field staff needs to ensure that credit unions that originate or purchase PSL participations comply with the rule and associated guidance.19

5. Field Staff Responsibilities

With sound processes and controls in place, private student lending can provide a valuable service to members and be profitable for credit unions. As with every product and service provided by credit unions, field staff will evaluate the strength of a credit union’s private student loan program and the level of risk to the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (Share Insurance Fund). Field staff will ensure credit unions offering PSLs have established:

- effective third party due diligence processes;

- appropriate risk-management systems and internal controls, including policies, procedures, and controls for originating, servicing, and monitoring the PSL portfolio; and

- qualified and trained staff.

The depth of field staff’s review will depend on the unique fact pattern for each credit union and the level of risk posed by the PSL program. When scoping a review, field staff scales the depth of the review to the:

- level of activity and risk exposure in relation to the credit union’s total loans, total assets, and net worth;

- size, financial condition, and complexity of the credit union;

- type of PSLs offered (e.g., direct or indirect whole loans);

- management’s risk-management practices and short- and long-term program goals;

- performance of the PSL portfolio in terms of delinquency and losses, and potential impact on earnings and net worth;

- staff expertise, infrastructure, and internal controls; and

- due diligence over third-party service providers, if applicable.

When there is limited risk exposure to PSLs, field staff’s review may be limited to a high-level review of policies, controls, reporting, and due diligence over third parties (when applicable). The scope of the review will be more comprehensive if the current or potential risk exposure is significant, including reviews of a representative sample of individual loans.

6. Additional NCUA Guidance Relevant to Private Student Loans

The guidance in this document builds on the following NCUA guidance:

- Loan Participation Waivers (LCU 13-CU-07)

- Indirect Lending and Appropriate Due Diligence (LCU 10-CU-15)

- Concentration Risk (LCU 10-CU-03)

- Evaluating Third Party Relationships (LCU 08-CU-09 and LCU 07-CU-13)

- Specialized Lending Activities (LCU 04-CU-13)

- Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (LCU 02-CU-09)

- Due Diligence Over Third Party Service Providers (LCU 01-CU-20)

Appendix C outlines recent guidance from other regulatory authorities.

7. Conclusion

Credit unions have increased their participation in the private student loan market to better serve members and diversify their loan portfolios. Private student lending can be a valuable member service and a good source of revenue for credit unions when done safely and soundly.

However, PSLs have unique features and risk characteristics that are unlike most other consumer loan products, and which must be properly understood and managed. Field staff will ensure that credit unions have carefully considered the risks, including the risk associated with any third-party providers, and mitigated them through strong planning, policies, procedures, and controls.

Appendix A: Comparison of Private and Federal Student Loans20

Both PSLs and federally guaranteed student loans generally: 1) require school certification to confirm the borrower’s eligibility based on the student’s registration status and associated cost of attendance; 2) allow for deferred repayment until a student leaves school; and 3) are not dischargeable in bankruptcy.21 The following table outlines differing characteristics between federally guaranteed student loans and PSLs.

| Private Student Loans | Federally Guaranteed Student Loans |

|---|---|

| No government backing | Federally guaranteed |

| Eligibility based in part on credit history, plus school criteria | Eligibility based on need or school registration criteria |

| May be variable- or fixed-rate, and contain additional term | Typically low-cost, fixed-rate, including needs-based subsidies for students |

| Administered by lender or private third party | Administered exclusively by the federal government |

Milestones in Evolution of Student Lending

The milestones below provide additional context to the student loan market.

- Guaranteed vs. Direct: From the mid-1960’s through 1993, financial institutions granted federal student loans, which were guaranteed by the federal government. Starting in 1993 through June 30, 2010, federal student loans could be either guaranteed by the federal government or borrowed directly through the federal government. As of July 1, 2010, all new federal student loans must be made under the U.S. Department of Education’s Direct Loan program.

- Privatization of Sallie Mae: In 1972, Congress established the Student Loan Marketing Association (SLMA or “Sallie Mae”) as a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE). Beginning in 1997, and completed by the end of 2004, Sallie Mae was reorganized and privatized. Sallie Mae is currently the largest provider of PSLs.

- Bankruptcy Reform: With bankruptcy reform in 2005,22 qualified education loans, as defined under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986,23 are generally exempt from discharge in bankruptcy. While this provides an added level of repayment assurance, it is not an ironclad guarantee of repayment. Student-borrowers without jobs and income sources may default regardless of the special standing in bankruptcy. If the borrower claims, and the bankruptcy administrator agrees, that the debt is overly burdensome (i.e., causes an “undue hardship”), the loan or a portion of it may be discharged under certain circumstances. PSLs are not supported or backed by federal, state, or local government.

- Dodd-Frank Act: The 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act requires the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to analyze PSL borrower complaints and offer recommendations to the Treasury Secretary, Education Secretary, and Congress.

According to the CFPB, the financial institution PSL origination market grew from less than $5 billion per year in 2001 to more than $20 billion per year in 2008, before contracting to less than $6 billion in 2011.24 The drop, which began in 2008, is a result of tightening credit standards (in particular, the increase in required co-signers), and a virtual collapse of the asset-backed securities market for PSLs.

During the boom period between 2001 and 2008, the PSL market resembled the subprime mortgage market, with high investor demand for Student Loan Asset-Backed Securities (SLABS). This allowed SLABS issuers to create structures with very low collateralization ratios. Since 2008, lenders have changed their underwriting and marketing practices, and the PSL market has contracted. For example, in 2011, 90 percent of PSLs to undergraduates required the school to certify the student’s need for financing.25 Lenders have also increased overall credit scores within their portfolios since 2005, and have increased the percentage of loans with a co-signer from 55 percent in 2008 to more than 90 percent in 2011.26

Default rates have spiked significantly since the financial crisis of 2008. According to the CFPB, the unemployment rate for PSL borrowers who started school in the 2003−04 academic year was 16 percent in 2009. Further, cumulative defaults on PSLs exceeded $8 billion and represented more than 850,000 distinct loans.27 Borrowers who are delinquent on their federal student loans can get relief through several programs, while delinquent PSL borrowers typically have fewer such options.

Current Trends and Status of Private Student Loans

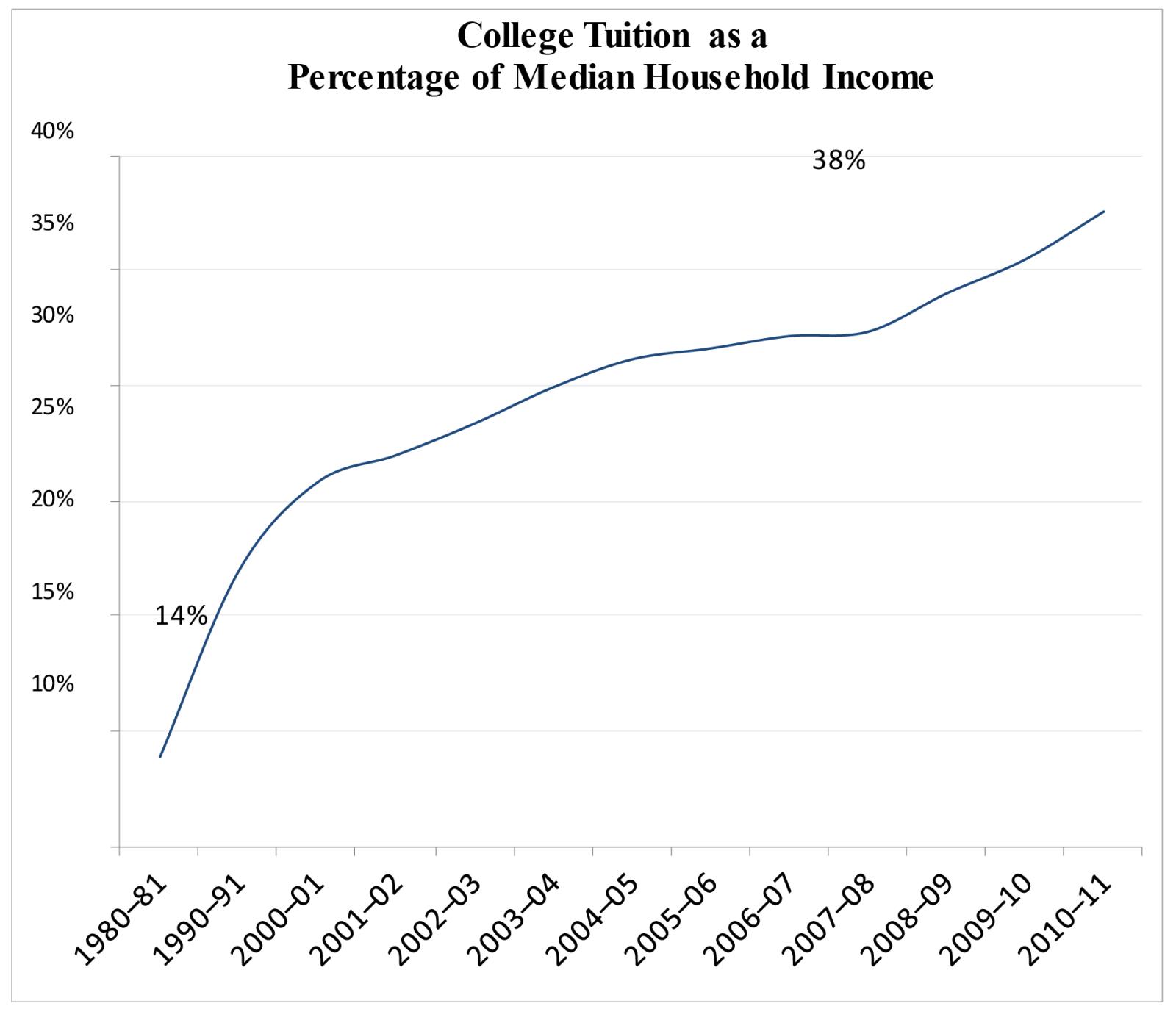

PSLs are becoming an increasingly important component of the educational finance equation for middle class families.28 Flat household income and college tuition costs have increased faster than the rate of inflation, resulting in a growing gap between what families can afford to pay (through income, savings, financial aid, and subsidized financing programs) and the total cost of a college education.

Since 1980, annual college tuition nearly tripled as a percentage of household income, widening the finance gap.

NCUA first captured PSLs on the 5300 Call Report in 2011. PSLs grew from less than $1.5 billion on December 31, 2011, to more than $2.0 billion one year later. As of December 31, 2012, 579 credit unions reported PSLs on the Call Report. At year-end 2012, PSL delinquencies and charge-off rates were 1.37 percent and 1.19 percent, respectively.

In May 2013, CFPB published Student Loan Affordability: Analysis of Public Input on Impact and Solutions, which further outlines recent interventions in the student loan market and explores the potential impact of student debt burdens.

Private student lending will likely be a growing component of education financing for most college students, presenting various opportunities and risks for credit unions.

| Opportunities | Risks |

|---|---|

| Replace business lost when guaranteed student loan programs were brought in-house with the federal government. | The level of national student debt is rapidly rising. |

| PSLs are a much-needed source of financing for students seeking higher education. | A slow job market and rising debt load have caused increasing defaults. |

| Opportunity to grow credit union membership and establish a relationship at the beginning of a member’s prime borrowing years. | Repayment is dependent on the promise of future earnings, driven heavily by the economy. |

| Product is compatible with the credit union mission. | The regulatory landscape is dynamic and changing. |

| Qualified Education Loans are generally exempt from discharge in bankruptcy. | Potential changes in bankruptcy laws could result in PSL losses being significantly higher than originally planned. |

Appendix B: Direct and Indirect Private Student Loan Comparison

Credit unions can originate private student loans directly or indirectly. The table below compares the differences between direct and indirect loan products.

| Issue | Direct Loans | Indirect Loans29 |

|---|---|---|

| Credit Union Membership | Potential borrower must be a member of the credit union before the loan may be approved. | Potential borrower may or may not be a credit union member before loan approval.30 |

| Loan Application | Potential borrower applies directly to the credit union. | Potential borrower applies directly to the third-party service provider. |

| Underwriting Standards | Credit union loan policies specify underwriting standards for PSLs. | Program guidelines specify the underwriting standards to which the credit union contractually agrees. |

| Loan Approval | Credit union loan officer makes the loan approval decision. | Third-party service provider makes the credit decision based upon program guidelines to which the credit union contractually agrees. |

| Loan Denial | Credit union loan officer makes the loan approval decision. | Credit union may or may not be allowed to deny a loan application that meets program guidelines. |

| Disbursement of Loan Funds | Credit union loan policies govern how loan funds are disbursed, and to whom. Disbursement of loan funds directly to the school is considered to be best practice. | Program guidelines determine whether loan funds are disbursed to the borrower or directly to the school. |

| Loan Standards (e.g., minimum and maximum loan amount, disbursement schedule, type of costs disbursements can cover) | Credit union loan policies dictate the loan standards and requirements. | Program guidelines establish loan standards and requirements. |

| Loan Repayment Terms (e.g., deferment, grace periods) | Credit union establishes loan repayment terms, which must be compliant with the Federal Credit Union Act, in their loan policies. | Program guidelines establish loan repayment terms, which must comply with the Federal Credit Union Act. |

| Interest Rate Pricing Structure | Credit union establishes the interest rate pricing structure. | Program guidelines establish interest rate pricing structure. |

| Annual Commitment | Credit union establishes goals and limits for each type of loan in their portfolio. | Credit union may have to commit to originate or purchase a certain amount of loans annually. A credit union that does not fulfill its commitment may be subject to a non-performance fee. |

| Default Insurance | Credit union can elect to purchase, or require the borrower to purchase, default insurance. | Some third-party service providers require default insurance. |

| Fees and Costs | Credit union determines the loan-related costs that may be passed along to the borrower in the form of one-time fee or annual fees. | Borrower may be subject to an initial origination or processing fee. Credit union may pay an initial set-up fee, individual loan origination fees, and/or monthly servicing fees. |

| Servicing and Collections | Credit union may service the loans in-house or outsource the servicing to a third party. | Third-party service providers generally service the loans, but may outsource functions according to program guidelines. |

| Regulatory Compliance | Credit union is responsible for ensuring the program, including all loan documents, comply with applicable laws and regulations. | Program guidelines to which the credit union contractually agrees specify which party to the agreement is responsible for regulatory compliance. However, the credit union must exercise appropriate third-party due diligence, since it is ultimately accountable for its compliance with applicable regulation. |

Appendix C: Recent Guidance from Other Regulatory Authorities

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued a joint release on July 25, 2013, encouraging lenders to work constructively with PSL borrowers experiencing financial difficulties. The release noted prudent workout arrangements are consistent with safe and sound lending practices and are generally in the long-term best interest of both the financial institution and the borrower.31

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s 2012 Annual Report of the CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman states:

“Community Banks and Credit Unions

A number of leaders from small financial institutions have expressed interest in developing long-term relationships with young customers but note many of them are unable to enter the marketplace due to their student loans. One way small financial institutions might assist younger customers move closer to homeownership is to offer products that allow refinancing of any student loans carrying rates in excess of their perceived repayment risk. Small financial institutions might even be able to assist customers worried about falling behind on student loans by offering products that might allow them to be successful.” 32

The most recent Annual Report of the CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman, released in October 2013, explores how “[r]ecent changes to mortgage servicing and credit card servicing industry practices may shed some insight on possible approaches to remedy student loan servicing programs.”33

While both the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Department of Education have made a series of recommendations to Congress to improve the PSL marketplace and address consumer protection issues, discussion of public policy issues is outside of the scope of this guidance.

Footnotes

1 Loans that meet the definition of a “qualified education loan” are generally exempt from discharge in bankruptcy, unless the borrower can show “undue hardship,” a relatively high standard. A qualified education loan can be either open-end or closed-end. US Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C. §523(a)(8); the “qualified education loan” determination is based on the use of the funds, when the funds are borrowed in relation to attendance at the educational institution, and whether the recipient of the funds is an eligible student.

2 Such as the number of disbursements allowed per year, minimum and maximum disbursement amounts, items disbursements may cover, and process for requesting disbursements.

3 Refer to the guidance contained in letter to credit unions LCU 10-CU-03, Concentration Risk, when reviewing a credit union’s policy limits.

4 Official cohort default rates for student loans are available from the Department of Education. See http://www.nslds.ed.gov/nslds_SA/defaultmanagement/search_cohort_2yr.cfm.

5 34 CFR 668 subpart M clarifies the loss of eligibility.

6 15 U.S.C. §1601 et seq., 15 U.S.C. §1693 et seq.; 15 U.S.C. §1692 et seq.; 5 U.S.C. §552a et seq.; 15 U.S.C. §1691 et seq.; 15 U.S.C. §57a et seq.

7 12 C.F.R. §§1026.46-48; and 15 U.S.C. §§1601 et seq.

8 12 U.S.C. §1757(5)

9 Open-end PSLs must meet the criteria in 12 C.F.R. §1026.2(a)(20), which include: (1) the lender must reasonably anticipate repeated transactions; (2) the lender may impose a finance charge from time to time on any outstanding unpaid balance; and (3) the amount of credit that may be extended to the consumer during the term of the plan (up to any limit set by the creditor) is generally made available to the extent that any outstanding balance is repaid. The last criterion means that the credit line must be replenished (i.e., payments made against a borrower’s balance must “free up” available credit at a commensurate rate) for a loan to qualify as open-end. See 12 C.F.R. sec. 1026.5 – 16

10 12 C.F.R. §§1026.5 -16; and 15 U.S.C. §§1601 et seq.

11 12 U.S.C. §1757(5)

12 20 U.S.C. §1083

13 Refer to the 2006 Interagency ALLL Policy Statement transmitted by Accounting Bulletin 06-1 (December 2006) for ALLL methodology and validation policy guidance.

14 See ACCTBUL06-01Policy

15 Some of the broad revenue recognition concepts include [FASB ASC 905-10-25 Revenue Recognition]:

- Revenue and gains are generally not recognized until realized or realizable.

- Revenue and gains are realized when products (e.g., goods or services, merchandise, or other assets) are exchanged for cash or claims to cash.

- Revenues are considered to have been earned when the entity has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues.

- Revenue should ordinarily be accounted for at the time a transaction is completed, with appropriate provision for uncollectible accounts.

16 12 C.F.R. §741.3(b)(2), App. C

17 The underwriting and approval/denial decisions for these PSLs are generally based on policies that are approved or adopted by the credit union, and may employ proprietary credit-scoring models.

18 See letter to credit unions LCU 08-CU-09, Evaluating Third Party Relationships Questionnaire (April 2008); LCU 07-CU-13, Evaluating Third Party Relationships (December 2007); and LCU 01-CU-20, Due Diligence Over Third Party Service Providers (November 2001).

19 12 CFR §701 – Organization and Operation of Federal Credit Unions and 12 CFR §741. See NCUA Letter to Credit Unions 13-CU-07, Loan Participation Waivers.

20 The terms “federally guaranteed student loan” and “federal student loans” are used interchangeably.

21 11 U.S.C. §523

22 11 U.S.C. §523

23 26 U.S.C. §221(d)(1)

24 See the CFPB report, Private Student Loans, issued to the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions; the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services; and the House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce on August 29, 2012.

25 Ibid

26 Ibid

27 Ibid

28 Source: College Board

29 Some indirectly sourced PSL programs are structured as whole loans owned solely by one credit union. Other programs are structured as loan participation arrangements involving multiple credit unions or other eligible organizations.

30 If a credit union funds a loan through or purchases a whole loan from a third party, the borrower must be a member of that credit union before the loan is disbursed. If a credit union purchases a participation interest in a loan originated by a third party, the borrower must be a member of a participating credit union before a federally insured credit union may purchase the participation.

31 FDIC, Banking Agencies Encourage Financial Institutions to Work with Student Loan Borrowers Experiencing Financial Difficulties (July 25, 2013).

32 CFPB, Annual Report of the CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman (October 16, 2012).

33 CFPB, Annual Report of the CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman (October 16, 2013).